A dangerous and lonely road

Lessons in good trouble from the woods of Freedom, Maine

Some of you might be aware that I love good dream-haunting horror movies—the slow burn types that take their sweet time cranking up the dread before unleashing the full cascade of horrors. And within this illustrious subgenre, it’s pretty difficult to beat The Blair Witch Project. I was too young to catch the film during its monumental theatrical run in 1999, when the found-footage genre was still a novelty. But I remember seeing the sparse trailers for the film around that time, and even those creeped the hell out of me. The premise is arrestingly simple. Three film students ventured into the woods outside of Burketsville, Maryland to make a documentary about a local legend known as the Blair Witch. The students vanished without a trace and exhaustive search and rescue efforts uncovered nothing. Three years later, the students’ footage was found.

You could spend an entire lifetime writing horror movies and never come up with a narrative pitch this good. The Blair Witch Project is entirely comprised of the “lost” video and film shot by the ill-fated students—which tells their story in a manner that feels more real and visceral than 99% of the movies you encounter in theaters these days. And while the actors who portray the students are all performing at the top of their game (they pretty much had to live in the forest for the duration of filming), the one who viewers tend to remember most is Heather Donahue. She’s the director of the documentary project that the three are shooting. When the students get lost and start hearing strange noises outside of their tent after sundown—the first of several escalating signs that someone or something is following them—Heather is the one who’s most in denial about how fucked their situation is. But eventually, the horrors unfold to such a degree that Heather’s forced optimism shatters. And what we get, toward the end of the film, is a confessional monologue from Heather in which she turns the camcorder on herself and tearfully apologizes to her family and the families of her fellow students, for leading them into the woods. It’s a last testament done as a selfie, many years before the era of selfies, and it should have made Donahue a star.

Well actually, it did. Kind of. But not in the way that lots of us like to imagine stardom. Audiences responded so strongly to The Blair Witch Project that some were unable or unwilling to separate Heather Donahue, the lead actor, from her character who is also named Heather—a character whose confidence and self-delusions make the students’ predicament worse. That Heather is portrayed as a strong-willed woman, unwilling to take the blame from her fellow (male) students until things have truly gone south, no doubt touched a deep nerve with some viewers in the late-90s moviegoing climate; a landscape with a lot of internalized misogyny. While Donahue was able to leverage her sudden celebrity into landing a couple of supporting roles in mainstream movies such as the Freddie Prinze Jr. comedy Boys and Girls, she struggled to find work, still trailed by the shadow of the Blair Witch. And eventually, in 2008, Donahue retired from acting.

It was a decision that would lead Donahue to a different woodland in Freedom, Maine. And up here, within the town’s vast forest, is where this week’s story really begins.

As reported by Steve Greenlee for The Boston Globe, in a feature story that I strongly recommend reading alongside this one, Donahue became a Maine resident in 2017, after working as a medical marijuana farmer, writing a memoir, and launching a life coaching practice. This, plus a local gardening job, allowed Donahue to buy a small plot of wooded land in Freedom, where she spent a summer hiking and swimming. This was her gateway to off-grid living—she built a solar-powered house on the land after the first summer—but it was also Donahue’s surprise window into local politics.

As Donahue spent more time hiking in the surrounding woodlands, she became aware of a controversy surrounding Beaver Ridge Road—specifically a 1.5-mile portion of the road that’s basically a dirt path through the woods. Like others, Donahue had walked this path several times when she found out that the general public’s right of access to the path was being contested by homeowners whose property abuts Beaver Ridge Road. Some homeowners had begun putting up NO TRESPASSING signs on the path. Their argument, that the Town of Freedom had long since ceased maintenance of this piece of the road, was bolstered by accounts of snowmobilers and ATV riders making use of the road and creating enough of a ruckus to justify closing the road to the public; even to passive users like Donahue, who were just walking there.

This was one of the things that inspired Heather Donahue to run for Freedom’s Select Board; an interest in land stewardship, concentrated around the Beaver Ridge Road brouhaha. In New England towns, a Select Board is basically the executive branch of government. It’s a collective body charged with making policy decisions on a range of local issues. Donahue won a seat on Freedom Select Board in 2024. And according to accounts from the Globe, the Midcost Villager’s Carolyn Zachary, and the Portland Press Herald’s Hannah Kaufman, the board decided to tap Donahue as their Beaver Ridge Road taskmaster. This is what led to Donahue poring over decades-old maps of the road to determine its historic precedent as a public way, to help build the town’s case for keeping Beaver Ridge Road completely open to the public. Her work took on a new level of urgency when the lawyer representing one of the homeowners sued the Town of Freedom, which caused the town to accrue thousands in legal fees. It was a common escalation for Maine, where 94% of forested lands are privately owned, and there was a good chance that the Town of Freedom would lose the case.

And that’s when Donahue did something that shocked the Select Board and the town.

To illustrate the former arc and dimensions of the lost 1.5 miles of Beaver Ridge Road, which had since eroded into a rugged dirt trail, Donahue walked the path with a can of orange spray paint and marked some of the trees with large X’s. For the homeowners, this was a bridge too far. They insisted that in marking the trees on the path, Donahue had stepped onto private property and defaced it. Counter-arguing that the trees were on public property—IE, the footprint of the disappeared portion of Beaver Ridge Road—Donahue had once again touched a nerve. In Maine, private property rights tend to be treated as sarosanct. Even though the State of Maine stipulates that private property without any visible No Trespassing signs is fair game for passive recreation, the state also insists that anybody wishing to recreate on such lands must obtain permission from the landowner first. So it’s not much of a surprise that Donahue found herself facing a recall vote after spray-painting the trees. 122 residents of Freedom chose to kick Donahue off of the Select Board, defeating the 91 who voted against her recall.

One week later, the Freedom Select Board held a vote of its own—declaring whether or not Beaver Ridge Road was a public space that should stay open to the public. It was the culmination of Donahue’s research, and while Donahue herself was unable to take part in the vote, the Board ultimately decided that the road is indeed a public space.

I think there are two reasons why this story has been garnering so much coverage from our regional media. The first and most obvious is Heather Donahue’s connection with The Blair Witch Project. New England is somewhat starved for celebrity stories that don’t involve profesional athletes or the Wahlberg brothers. Anything concerning someone whose work is nichier is going to command attention. But the other reason why I believe that Donahue’s expulsion from a small town Maine Select Board was a headline story is because so many of us have found ourselves in Donahue’s position over the last few decades—outdoors and loving it, enjoying a walk across a beautiful stretch of countryside, only to happen upon a big NO TRESPASSING sign that wasn’t there the last time you visited. (A sign that might not even be legal!) The homeowners living alongside Beaver Ridge Road who tried to stop the wider public from using the dirt path segment of the road represent larger forces that many of us will recognize all too well; widening distrust in each other and an impulse to dominate what’s around us.

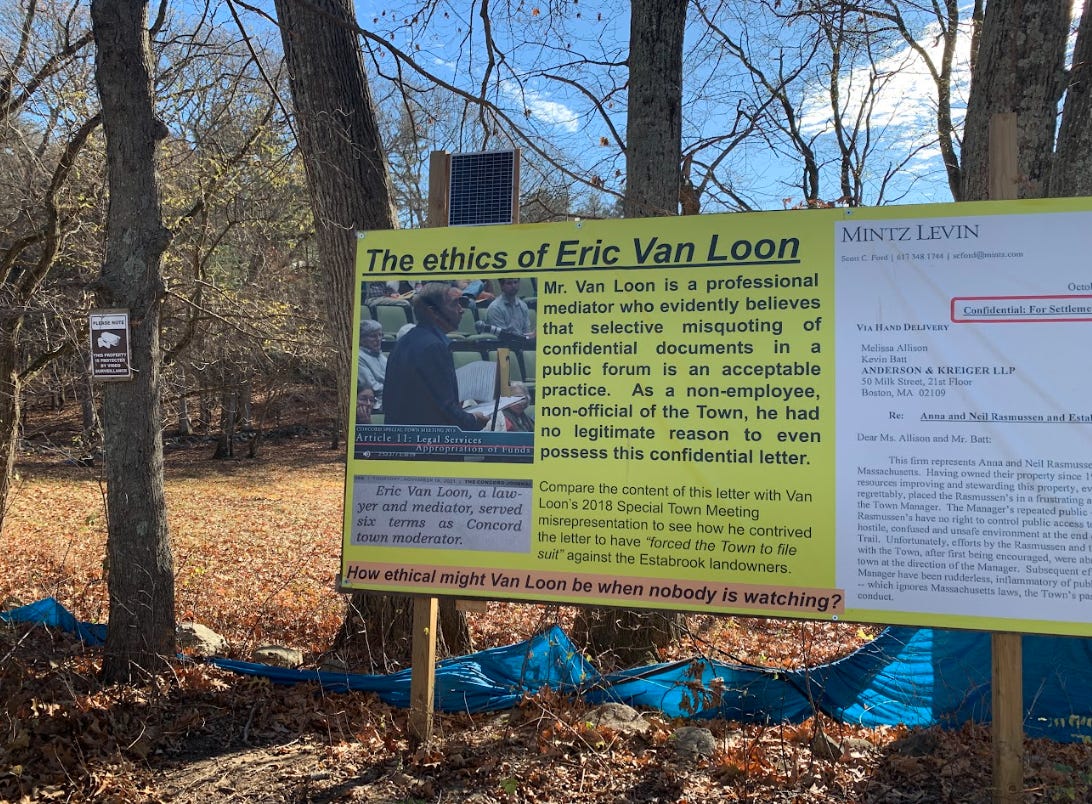

Last fall, I learned about a similar road of controversy in Concord, Massachusetts; the tony little hamlet with gorgeous forest paths connecting to neighboring towns’ trail networks. Estabrook Road, which runs around two miles from Carlisle into Concord, has also deteriorated to the point where much of the road now resembles a pathway through woods and meadows. And just like the Freedom, Maine situation, a group of homeowners whose properties abut Estabrook Road have been posting their own NO TRESPASSING signs along the segment of the road that passes their properties, and waging a legal argument that the road is part of their private domain. This case grew so contentious that back in October, the Massachusetts Court of Appeals weighed in and ordered the homeowners to stop installing the signs. That was how I found out about the legal battle. So I decided to go and check out Estabrook Road for myself.

When I reached the contested segment of the road, I was surprised to find several signs there. These were not anti-trespassing signs, however. They were miniature billboards, designed to ellicit sympathy for the homeowners. The largest featured extensive written legal arguments in their favor, and it had loudspeakers attached to the edges! From the speakers, you could hear an audio loop from the most recent hearing; specifically the bits where the homeowners are lamenting the nuisance of having other people walking by their homes each day. It must have cost at least $500 to create these signs. And then there was the unquantifiable cost of the homeowners’ disrupting their own peace and quiet, by blasting courtroom audio through the trees.

For me, this demonstrated something that a lot of us need to understand and accept. The forces of exclusion and dominance—the same forces, I would argue, that have seized our federal goverment—are willing to fight like hell and throw out all the stops, when it comes to guarding what they perceive as theirs. And even if we’re committed, to the notion that pushing back against these forces must happen within the realm of our legal system (something which I basically agree with), laws are not always going to stop people from claiming something that doesn’t belong to them. So….then what?

I’m not sure if painting X’s on trees that may or may not grow on public property would qualify as an act of civil disobedience, in the most technical sense. But in spirit and in practice, the action that led to Heather Donahue getting booted from Freedom’s Select Board does feel like of an engagement in civil disobedience. For me, it registered as someone resisting our learned deference to power, which often holds us back from bringing a real knife to a knife fight, legally speaking. And it’s also a reminder that civil disobedience that may initially ruffle feathers has a way of moving public consensus. Would the Town of Freedom have voted to keep Beaver Ridge Road open to the public if Donahue hadn’t drawn attention to the issue by marking those trees? It’s possible that Donahue’s archival research alone might have persuaded a majority of the Select Board, when it was time to vote on the issue. But how much thought would the board have given to the issue, if the dispute hadn’t been moved into the limelight? It’s actions like this which can snap us out of apathy and cause us to go, “Hey, hold on a minute….”

What I do know, however, is that people who decide to take action will often remain uncredited if their actions help bring about positive changes. And in many cases, the consequence of civil disobedience can follow you; impacting your ability to find work or to lead a peaceful life. There’s a not-zero chance that one of your favorite trails or roads for walking may have been the subject of a legal spat at some point. Someone could have gone to jail or lost a job, after standing up for public access to that trail or road. Take a moment and wonder, Where are they now? Where did the trail lead them?

Donahue, for her part, is still firmly rooted in Maine. Maybe even more so than before.

“Public access to woods and waters, self-sufficiency, food sovereignty and home rule are all worth fighting for,” Donahue said to the Midcoast Villager. “It seems in such a forested town as Freedom, there should be a place to take a walk in the woods.”

In my town, it's a gate that was put across a 30 foot length of sidewalk that connects two parts of our bike path network in town. The alternate route makes you cross a busy four lane road where people routinely speed. The bikers and runners have lost several court cases, and I find the gate morally reprehensible before you get to any legal arguments. I attended a "bike race" organized in protest earlier this spring. The gate's still there but it was cathartic to do something.

Miles, great reporting. And good writing. Always appreciated. I believe it is a right of citizenship to claim back right-of-ways wherever they have been compromised. Clam flats in Hingham, public property to the high water mark until new property owners decided they took exception to that freedom. Shell fishing rights from the earliest days of the Pilgrims! Shell fishing prevailed but not without legal fees incurred.