When you leaf through a lot of hiking guidebooks and websites, you start to notice funny patterns in the New England landscape: like the striking number of hikes with names that invoke the devil and/or general hellfire. (I wrote a newsletter about that!) Or the fact that there are four different peaks in New England called “Mount Misery.” And invariably, these peaks are absolutely beautiful destinations that a normal person would associate with a mind as blissed-out and glassy calm as the Ipswich River.

My theory is that the Mount Misery moniker, like so many New Englandisms, began with the colonization of the landscape by the Puritans. Imagine: you’ve just fled from persecution in Europe, you’ve arrived on unfamiliar shores, and the mysterious woods and hills beyond the beach are the perfect canvas for your anxieties and superstitions. When you’ve got a haunted mind, it’s very hard to appreciate the natural splendor of the countryside. The hemlock trees become creaking sentinels, staring down at you menacingly. The moss bristles with evil, perhaps conspiring to swallow you whole.

Most of us have been here before: outside at the wrong mental moment, when nature seems to refract our troubled thoughts. Last Wednesday, I was not happy. A surprise flat tire had just burned a $140 hole in my wallet, and I had read one too many articles about the rise of AI and the worsening devaluation of creative writing. And suddenly, it occurred to me that this moment could be an interesting time to climb one of New England’s Mount Miseries. Would going there in a foul mood open up some hidden dimension of the place that I wouldn’t be able to see and appreciate with a chipmunk-cheeked grin? Even amidst my brooding and self-pity, I was determined to find out.

First, I had to decide which Mount Misery I would climb. The ones in Maine and New Hampshire would require bushwhacking, which seemed like a gateway from feeling grumpy to going insane. And I was already familiar with the Mount Misery in Lincoln, Massachusetts, which can be used as a literal gateway to Walden Pond each summer (if you’re up for an easy hike of a few miles.) This left one clear choice. Connecticut.

The Nutmeg State’s Mount Misery is nestled within 26,477 acres of greenery at the Pachaug State Forest. Located near the Connecticut-Rhode Island state line, the forest connects six towns and it’s the ancestral land of the Mohegan, Narragansett, and Pequot tribes. Much of the 17th Century war between English colonists and the tribal alliance led by Metacom was fought in these dense woods. But today, the site that draws a fair number of visitors to this quiet, overlooked place isn’t Mount Misery or the history of the forest. It’s the rhododendrons that grow in the wetlands there.

Granted, my angst-ridden focus was still Mount Misery, but the prospect of seeing Pachaug’s rhododendron sanctuary in full bloom was an alluring bonus. So I headed south, with granite colored clouds congregating overhead, and entered the forest on Stone Hill Road. The density of the state forest trees had a striking effect on the light as I crept down a dirt road past several small pullout areas where one could park. Pachaug State Forest is a patchwork of roads and trails that intersect quite regularly, and you have a lot of freedom in designing the route of your hike here. My plan was to access the rhododendron sanctuary via the Cedar Swamp Trail (true to its name, it passes through a rare inland Atlantic Cedar Swamp!) From there, I would pick up the short, steep trail to the summit overlook on Mount Misery. The return would involve a descent into a vaster stretch of wetlands and tranquil road walking. 5.7 miles total.

The rhododendron sanctuary might be the top draw for Pachaug visitors who need their woody plant fix, but the dirt road that led me to the Cedar Swamp Trail was positively exploding with white and pink laurel flowers. The beautiful little buggers gave the hike a perfumy essence, as I scanned the woods for the swamp trailhead and wondered if I would make it back to the car before the afternoon’s projected thunderstorms settled over the forest. I found the entrance to the wetland path next to Edwards Pond, which seemed like a missed opportunity to imbue another gorgeous place with an improbably melancholic name. Why stop at mountains when you could also go swimming in “Affliction Lake” or wander through “The Meadow of Regrets”?

The impressive, bayou-like corridor through the cedar swamp led me to a spur path on the left: a connection to the rhododendron sanctuary. Sure enough, the scale of the rhododendrons was wild. I felt like I was stalking through some remote forest in the deep south. The droopy leaves were so thick in places that you had to gently push them out of the way. But as I reached the boardwalk section of the path, it became clear that I had arrived too early to catch the flower bloom. This is good news for all of you, because you could still head there and catch the event! But for me, already somewhat crabby, it was another stroke of misfortune to brood about. And it couldn’t have happened at a better moment. Because my next stop was Mount Misery itself.

I can’t speak for the Maine and New Hampshire versions of Mount Misery, but one in Massachusetts doesn’t offer a view. (It’s more of a wooded lump with wandering trails that connect to fields and streams nearby.) But Connecticut’s Mount Misery has exactly what you would want on such a peak—a ledge with a view of the undeveloped woods. The perfect place to meditate, smooch, or scream at the sky, depending on your mood. The trail to the summit is short and efficient, never too exposed but steep enough to make you crave a change of clothing. And once again, the vegetation felt decidedly foreign for New England. The trees emerged from an ocean of green ferns that would look right at home near Seattle. And the sense of enchantment that I got from these ferns was chipping away at my resolve to be miserable on Mount Misery.

After reaching the ledge, I assessed the cloud cover and the moisture in the air. The darkening sky and dewey atmosphere were pointing toward an imminent cloudburst. And I had a choice to make: stick to the original loop hike plan, or shorten the hike by taking the Mount Misery summit access road back to the rhododendron sanctuary and backtracking to the car from there. Rather impulsively, I chose the access road. And within a minute of turning right onto the dirt road, the Pachaug State Forest landscape transformed into one of the most bedazzling sights I’ve seen on a New England hike in months. The trees gave way to an expansive hillscape of ferns, odd looking plants, and occasional lone arbors. The woods through which I had been hiking lurked in the background, but the open land through which the access road ran was the star of the show here. Beneath glowering, rumbling skies in the soft light of the late afternoon, Mount Misery had become spectacularly austere and foreboding.

I made it back to the car just as the first raindrops began pattering against the laurel leaves, but even if I hadn’t been so lucky, the unlikely magic of the hike wouldn’t have been ruined. When you’re feeling down and the natural world seems to mimic your thoughts, the experience can have a variety of outcomes. It could make you feel worse (ex: slipping on wet roots and sliding into a ravine) but it also might make you feel less alone in your frustration or sadness. Walking down that lonesome access road from the summit of Mount Misery had the air of an unexpected communion with something much bigger than myself and no less alive. And as I drove home that evening, reaching for the radio dial as NPR launched into another story about AI and its potentially ruinous impact on creative labor, the gallons of rainwater that pounded against the windshield started to feel less like a nuisance, and more like a balm.

Mount Misery via Pachaug Rhododendron Sanctuary

Hike distance: 4.7-mile loop

Elevation gain: 285 feet

CLICK HERE for a trail map

One way to avoid the kind of basic yet expensive car maintenance that put me in a shitty mood before my Mount Misery hike is to ride mass transit to trailheads. And since we’re officially into summer, I must put in a sincere plug for Ridj-it. This Greater Boston-based platform is used by hikers to organize carpools for trips in the New England backcountry and they also operate The Mountain Flyer—a bus that offers roundtrip service from Boston and Salem, NH to popular White Mountain trailheads such as Lafayette Place. I once interviewed Ari Iaccarino, one of Ridj-it’s co-founders, for a story about opening up access to Massachusetts’ absurdly privatized coastline with buses that take people to public beaches. The way he described drivers staring with saucer eyes as the bus rolled into trailhead parking lots that had reached full capacity was all the reason I needed to commit to trying the Flyer myself sometime this summer. Imagine: napping after climbing Lafayette. Maybe we’ll be seatmates!

In other summer news, it’s been slim pickings at movie theaters lately (especially if you’re fatigued of superhero movies) and so, I’ve been thinking of films that have the sheen of summer weather—atmosphere so tangible that you can feel the mist of a thunderstorm or the merciless glare of the sun. Here’s what I’ve come up with so far. If you’ve got any suggestions, I’ll add them to the list:

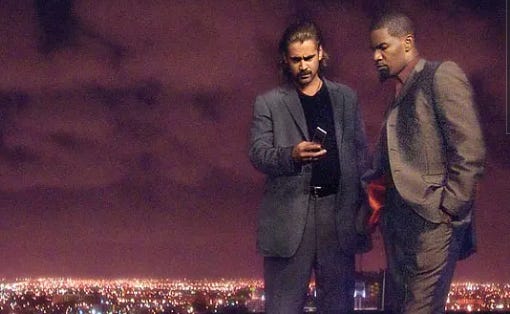

1. Miami Vice (2006): The digital photography of nocturnal Miami does a remarkable job of capturing the energy of those inevitable cloudbursts. And on a broader note, this mid-2000s adaptation of the TV series is much better than people gave it credit for. Darker, yes, but intoxicating in that inimitable Michael Mann way.

2. Do The Right Thing (1989): Modern movies seem to have any sense of grit or imperfection polished out of them, but just thinking of Spike Lee’s classic depiction of midsummer Brooklyn as a pressure cooker of racial joy, hatred, and confusion makes me want to take a shower. It’s like the celluloid is sweating. Relatable.

3. Call Me By Your Name (2017): For the most dreamlike manifestations of summer—the hazy twilights, the sun on the leaves, the clinking of cutlery and glasses from a garden—you can’t do better than Luca Guadagnino’s adaptation of the André Aciman novel about the spontaneous, life-changing nature of desire.