Usually, when weather turns deadly, our natural response is to flee the scene for safe havens. One of the more horrifically conceivable scenes that came out of LA this week involved hundreds of stranded motorists stuck in gridlocked traffic on the freeways, abandoning their cars, and continuing on foot as the ongoing wildfires crept closer. But in 1993, Malibu-based Pepperdine University took a very different approach to wildfire survival. You see, some of the university’s largest facilities were designed and built to be as fireproof as modern structures can be. And last December, when 20,000 Malibu residents were urged to evacuate as the Franklin Fire fanned across the hills, Pepperdine students stayed put and took shelter inside their fireproof library and campus center. And everybody made it out. The protocol worked! This time, at least.

Sheltering in place is almost always talked about in the context of episodes like the Pepperdine story—a temporary act of do-or-die necessity. By extension, the spaces that we think of as emergency shelters rarely facilitate more than sitting around and waiting for that heavenly moment, when it’s safe enough to open the door and emerge. But in cities that experience more regular and prolonged weather events that occupy the liminal space between “uncomfortable” and “it will literally kill you,” there’s a much longer definition of what qualifies as weatherproof shelter. Because at this point, you can’t just sit and wait. You have to keep on living and going about your daily errands and obligations, even as the punishing weather forces you to spend your days inside.

Enter the underground city—a network of subterranean passageways that connect the busiest buildings and subway stations in a city center. The idea itself isn’t particularly new. Many American cities have tiny examples of underground city passages, like the tunnels that connect Madison Square Garden to Penn Station and Moynihan Train Hall. But in the snowbound and frostbitten locales of North America, certain cities take the underground city concept to a more stratospheric level; with labyrinths of building-to-building passageways that you could spend an entire day or night wandering around.

Last winter, I flew to Edmonton for a travel industry event, and I arrived one day early due to the weather forecast. With extra time to explore, I made plans to go out, but I was immediately humbled by the reality of what Edmonton is like in early March. It was so fucking cold that when I walked two blocks from my hotel to a movie theater where Dune 2 was playing, I had to put on four layers, cover my face with a scarf, and use my eyeglasses for wind protection. I didn’t see a soul on the sidewalk. The next morning, when I made a 0.2-mile voyage from the hotel to an overlook from which I could see the Edmonton River Valley greenway (largest urban park in North America!), the city streets were comparably empty. The frozen city looked abandoned. And then, lured by the possibility of a Tim Horton’s kiosk, I pushed open the door to a building that was caked in ice. Quite suddenly, the people of Edmonton revealed themselves.

There seemed to be hundreds of them; traipsing past me in fur-lined parkas, lugging shopping bags, and enjoying their coffees on benches flanked by blooming greenery. The glass-ceilinged atrium we were sharing in the Edmonton Convention Centre is one of the more remote access points for Edmonton’s own underground city—the Pedway.

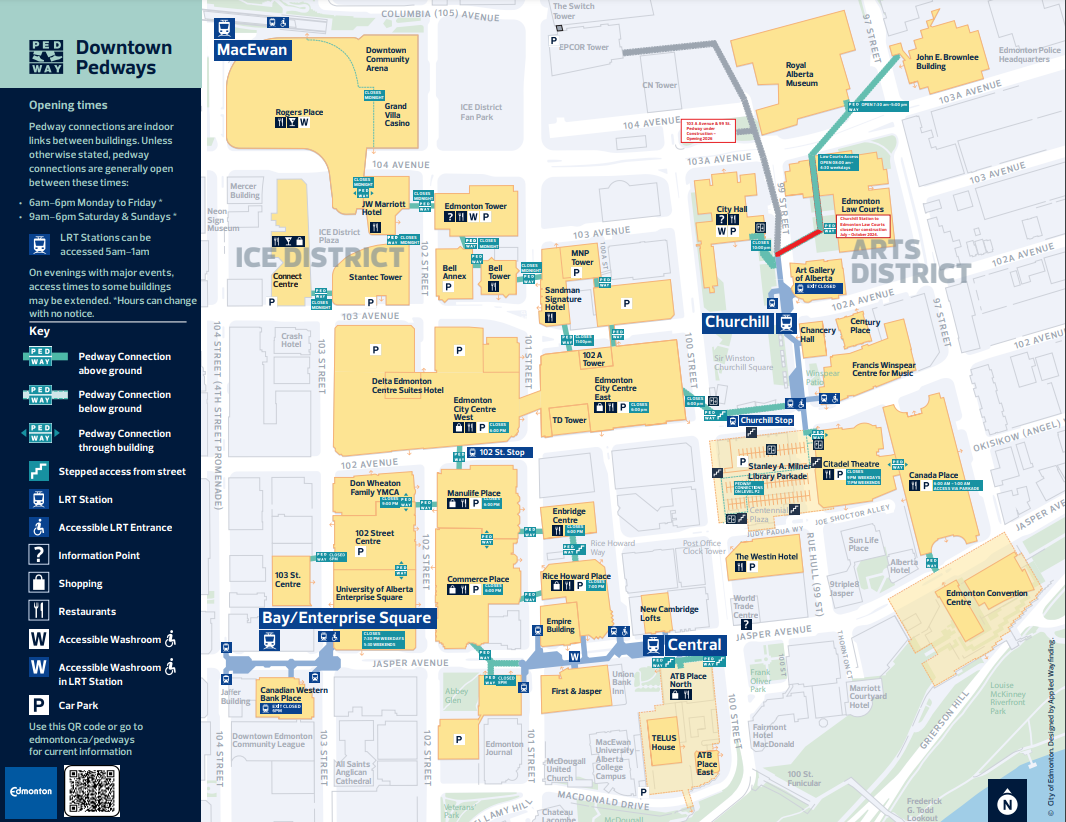

Upon reviewing a map of the tunnel network, I wondered how easily I could walk from the convention center to the ice hockey arena and casino at Rogers Place. It would be a solid northwesterly walk that would include some other curious buildings; Citadel Theatre, the Stanley A. Milner Library, and as convenience would have it, my hotel! The distance appeared to be less than a mile, but what I didn’t yet realize as I set off into the Pedway with unearned confidence was that determining which doorways and passages are part of an underground city route is half the fun of exploring the maze.

Most underground city routes are marked like a trail in the woods—with consistently branded signage that clearly indicates “Walk This Way.” However, these signs are not always posted by each turning point. And furthermore, the appearance of the tunnels themselves can vary quite a bit. Since the tunnels begin and end in different buildings, with different management and architectural styles, no connective tunnel is ever quite the same as the next one. Some are soft-lit and decorated with artwork, while others have a more austere and foreboding look. And to make matters even trickier, not all underground city passages stay beneath the surface. Sometimes, you might have to climb a flight of stairs and pass between buildings in a protected pedestrian bridge, before taking another set of stairs back into the subterranean level on the other side.

I encountered these obstacles several times during my inaugural Edmonton Pedway walk. It took more than 15 minutes of poking around the indoor gardens at the Tucker Amphitheatre before I found the stairs that took me down to a longer tunnel leading to the Edmonton City Centre East shopping mall. And by the time I reached the mall, my backside was a little sweaty and I had probably logged well over a mile on my soles already. In a way, exploring an underground city is a slightly more adventurous spin on Mall Walking—the increasingly popular art of walking laps around a shopping mall, if the weather outside is too nasty for sauntering. The fact that Mall Walking is having a moment really illustrates the widening need for spaces that are safe and strollable. I love that people are reclaiming malls as spaces for recreation, and the underground city concept and the mall are cousins; climate-controlled spaces that were made for commerce but function quite beautifully as explorable, low-barrier Adventure Zones.

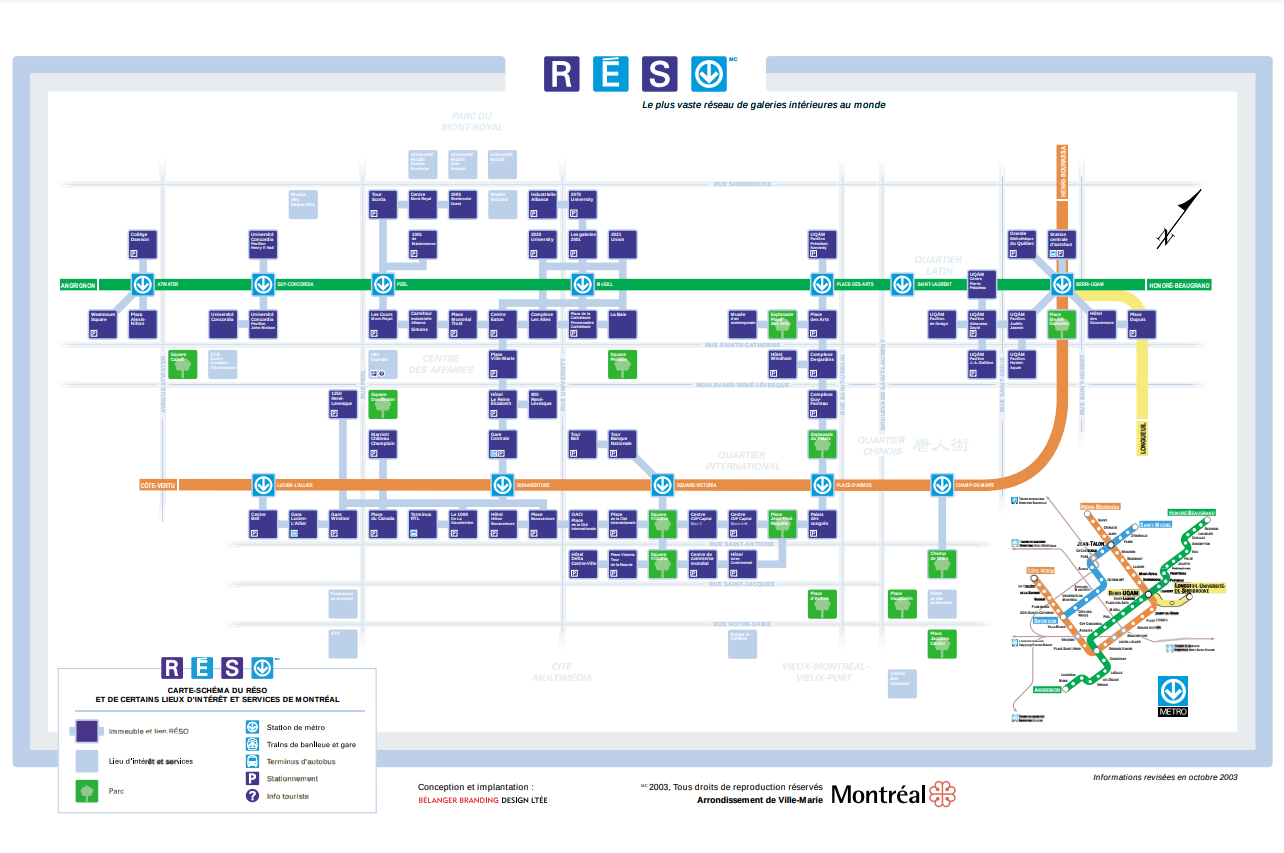

The difference is that you have lower odds of getting truly lost in a mall, compared to an underground city. And that’s why this past week, while visiting Montreal with my friend and fellow foot traveler Katie Metzger, we saved our traverse of Montreal’s own underground city—the RÉSO—for the last night of the trip. After two prior evenings that involved eating noodles and sampling dark beers at various nooks, we wanted to do something that pushed us beyond what’s familiar, when it comes to a night on the town. So, as Katie herself put it, we decided to have ourselves a night under the town.

We were staying two blocks aware from the Square Victoria Metro Station, where you can pick up the RÉSO labyrinth. And to ensure that we would stay in the underground city, we only wore enough cold weather layers to survive the 5-minute walk from the hotel doorstep to the subway entrance. Once we were in, we were IN. We would find our way to the Centre Eaton mall for dinner, before retracing our steps to a junction and pressing ahead in another direction to reach the Place des Arts performing arts center, where we would find…who knows? Underground sculptures? A wall of video screens featuring people in the great outdoors making shadow puppets of animals with their hands? A guy who looked like Jeremy Irons’ twin emerging from a theater?

None of these are hypotheticals. Katie and I encountered all of these sights in the last stages of our two-hour RÉSO journey, which was fueled by mall fudge and avoidance of the punishing weather on the surface. Some of the spaces we explored, such as the mall and the Gare Central train station, were predictably flush with Montrealers. But on more than one occasion, we had a connective tunnel to ourselves—the kind of tunnel where most people wouldn’t want to linger, given the dim quality of the lighting and the desolate appearance of the space. And I’ll be honest; roaming the RÉSO like a pair of mole people did start to mess with our heads. The back-of-mind awareness that all of this was a construct, powered by electricity and heating, made me crave the raw sensation of the wind in my face. So when we finally returned to Square Victoria to make the electrifying, above-ground dash to the hotel, there was a rush of catharsis.

Still, if we’re going to be dealing with increasingly dangerous and destructive weather for the rest of our lives—and if cities are best equipped to become bulwarks against gnarlier weather—I’d much rather live in a city where the weatherproof shelters are vast enough to accommodate movement and exploration; two of the most essential pillars of our lives, which many of us don’t miss or think about until they’re suddenly yanked away by circumstance. And while underground cities such as the Montreal RÉSO or Edmonton’s Pedway may sound like pipe dreams for U.S. cities, consider again that some of the infrastructure is already in place. In Houston, one of the muggiest places I’ve ever set foot in my life, there are six miles of air-conditioned underground tunnels that connect various buildings downtown. I know this because when I went there back in 2021 to report a story for the Rotary International magazine, I really, really wanted to go into the Houston tunnels to avoid the drenching mid-August heat. But my schedule was too busy to allow a solid afternoon of exploring the passages. So I settled for the air conditioning in my rental car and vowed to go into those city tunnels another day; hopefully just for fun, and not for survival. But in all likelihood, it will be a bit of both.

Given the weather events of late in LA, I’d like to use the end of this week’s Mind The Moss to direct your attention to this rolling roundup of GoFundMe campaigns which have been verified by GoFundMe as fundraisers for individuals and families who’ve been directly impacted by the wildfires. In addition, the Los Angeles Times has a very helpful list of organizations that are doing important ground work in LA as we speak.

If you’re based in LA or if you know anyone who’s based in LA, one crucial resource is 211 LA, a nonprofit organization that specializes in connecting people in need with temporary housing options. And since demand for temporary housing over the next several weeks will be huge and historic, Airbnb and a number of hotel brands have offered free or heavily discounted rooms to LA residents and travelers who’ve been stranded by the fire. Maya Kachroo-Levine just wrote about this for Travel + Leisure.

Still, I would refrain from heaping too much praise on Airbnb here; given the role that the company has played in worsening a residential housing shortage in cities around the world, and considering how severe that shortage is about to become in LA when the fires are out. Temporary housing for those impacted by a disaster is just that, and pretty soon, we are going to need to build a hell of a lot more housing in general, in SoCal and elsewhere. So, let’s get used to helping each other and sharing resources.

Cool (freezing cold!) article as always. It was so cold here last week that I resorted to short underground walks in the subway tunnels and the fairly long (1.5-2 miles) enclosed walk from the Hudson River through the Oculus to Fulton St. connecting frigid stretches outdoors.

The description to discovering the Pedway- made me feel like I was reading a scene from Harry Potter. Magical! Thanks for lifting up the resources and sharing thoughts on the events out in LA too ❤️