For a region that gets so sweltering and sticky for nearly one third of the year, New England is weird about swimming holes. Or rather, New England has a bizarre and frankly outrageous tradition of blocking public access to the ponds and lakes that could easily serve as swimming holes. It’s not that states themselves want to keep these water bodies swimmer-free. The problem is that many of our ponds and lakes are surrounded by private property. And states are reluctant to ask property owners to share a sliver of their land, so that a public easement path to the water could be built.

But even if New England’s elected governments were to prioritize compromise fixes like this—as a way of opening up more swimming holes to the sweaty masses—we would still have to deal with homeowners who’ve grown so accustomed to enjoying pristine waterfront views that the thought of sharing it with others has them reaching for their metaphorical or literal shotgun. A couple years ago, my housemate Kenneth decided to cool off after a toasty day of farming by going for a swim at the fittingly named “Farm Pond,” in the town of Dover, Massachusetts. He entered the pond from a lesser-known public access trail and he managed to incur the screaming wrath of a waterfront homeowner, for the grievous sin of dog paddling too close to his slice of the shoreline. And then we have the more prolific story of Chris Brady, a Rhode Island resident who decided to visit a formerly privatized beach in North Kingstown that the state had opened up to the public. This didn’t sit well with a local homeowner whose house abutted the beach. He confronted Brady and told him he had to leave. When Brady stood his ground and vocally defended his right to be on the beach, the homeowner responded by breaking Brady’s umbrella and throwing it into the surf.

These two stories are solid examples of what New Englanders are up against, when it comes to finding places to swim each summer. The barriers that we face are legal and cultural, and breaking down them will most likely happen in that order, with the cultural battle being a lot more drawn-out and messy. But what should we do in the interim? How do we deal with the ground reality that our summers are getting hotter and find accessible cool-down zones now, while our pestering lawmakers to finally do something about our swimming hole problem? In the absence of a movement or political momentum, we need to start sharing more swimming hole intel with each other! We each need to re-program the part of our brain that says, “I must keep this secret,” whenever we find a swimming hole that’s accessible and beautiful. And so, this mid-July weekend, I’m going to tell you all about how you can hike to one of the most swimmable beaches on one of New Hampshire’s most heavily privatized lakes.

If Lake Winnipesaukee is the McDonald’s of the New Hampshire Lakes Region, then the unquestionable Burger King is Squam Lake: the smaller and northerly neighbor of Old Winny. (I don’t know if anyone actually calls Winnipesaukee “Old Winny,” but I am.) Like the two cheeseburger titans, these lakes have a very similar look and feel, but in the same way that McDonald’s is a just little more eponymous than Burger King, the crowds for Winnipesaukee will always beat the Squam audience for size. Not only do Squam Lake residents like it that way, but the amount of private property surrounding Squam Lake all but ensures that the lake will remain inaccessible to the public. But just like every castle wall has a weak spot, the shoreline of Squam Lake has a rustic secret passageway to the waterfront: the Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest.

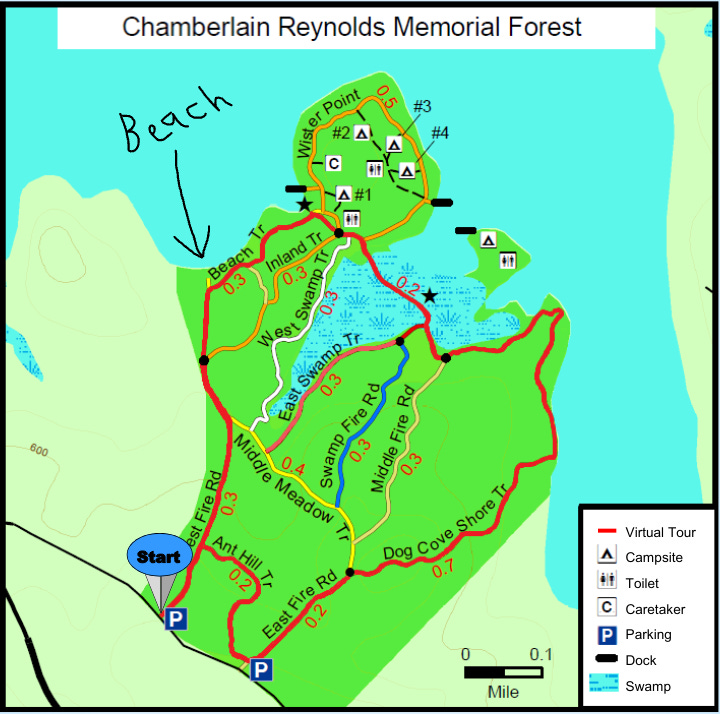

I realize that I’ve been doing a lot of griping about private ownership in this newsletter (and in others), but the Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest demonstrates how private landowners could be part of the solution to New England’s swimming hole shortage, while we work toward more muscular policy. This 169-acre woodland on Squam Lake’s southernmost shores, near the town of Holderness, is owned by the New England Forestry Foundation—whose mission includes “[Serving] the interests of all New England’s citizens by conserving forestlands and promoting the exemplary management of regional forests.” Notice how they specifically say “all New England’s citizens” here. The Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest strikes a positive balance between conservation and recreation. Because when you arrive at the doorstep of the forest, you can explore a spiderweb of trails that are managed by the Squam Lakes Association. The trails snake through mossy woods, a grassy wetland with wobbly boardwalk, and the leafy shoreline. Here you’ll find docks where you could launch a canoe or kayak, a small number of primitive tenting sites, and even an old pit toilet.

Now, before you grab your beach towel, there’s one caveat to bear in mind here. The parking lot for Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest is on the smaller side. By my estimation, on a recent visit, the lot can fit no more than 10-12 vehicles. This means you’ll need to be strategic when planning the hour of your hike-and-swim adventure. Visiting the region on the weekend? Get there early in the morning, or save the swim for the magic hour. The weekdays will offer a little more wiggle room, but the same windows still apply. If it’s a muggy day with a high dew point and cloudy skies, that could also be a prime time to visit the forest. And if you’re bringing friends, carpool!

The labyrinth of trails in the forest is relatively compact, so regardless of which ones you choose to take, you’re looking at a gentle hike of roughly 2-3 miles, with minimal climbing and descending. Hell, a lot of you could probably do this hike in your water shoes or sandals! On my first ramble here, which I took during the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic (I was on a socially-distanced camping trip and the showers at my campground weren’t working), I rather enjoyed the East Swamp Trail, which offers glimpses of a full-on swamp that’s fed by Squam Lake before taking you through the depths of the swamp itself on a long wooded walkway. From there, I connected to the Wister Point Trail and walked the periphery of what I assume was Wister Point: a little peninsula that juts out into the lake. This is where you’ll find the docks and tent sites. Through the trees, I could see a bunch of younger guys in a souped-up motorboat and as they puttered around in the water, I wondered if they could see me too. Standing in the trees, on this shaggier segment of such a developed lakefront, I felt like a deer staring into someone’s expansive backyard. And I hadn’t even reached the beach yet.

While you could scramble down the shoreline to the water in several places along the Wister Point Trail, the best swimming spot in Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest is located on the northwest edge of the woodland, and the conveniently-named Beach Trail is your best bet for reaching the sandy, sporadically rocky hideaway. And once you reach the beach, you can admire the totality of Squam Lake to the north. On clear days, you can also see the Sandwich Range of the White Mountains, looming above the northern waters. I hiked into the beach back in May, just to revisit the space and to make sure nothing had changed for the worse, as far as public access goes. (That’s why these photos of the woods and the waterfront don’t look very summery.) The hike was as seamless and serene as I remembered, and as I approached the beach, I saw that it was partially occupied by a couple, sitting on some stones and, I shit you not, playing mandolins. Their yellow lab, meanwhile, was going for an invigorating swim.

There’s this infectious supposition that if we make stuff like this possible at more of our ponds and lakes, people will show up in massive numbers and ruin them, leaving litter and other detritus in their wake. This can happen, but it’s generally contained to swimmable areas that don’t involve hiking in. And these areas are often managed by state and town offices, with the resources to deal with inevitable shitty behavior from some visitors. Policies that essentially create more public swimming holes will have to include good management plans for the most broadly accessible ponds and lakes. But swimming holes that require a short-to-medium hike through a managed green space like Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest can often survive and flourish with a lighter touch. And that’s because these green spaces tend to inspire a more humble approach from visitors and volunteerism among fans. So if you manage to wade into Squam Lake this year, via any of these gorgeous trails, you might consider returning and spending a day or so doing trail maintenance with the Squam Lakes Association. And when you get home, tell your friends and family about the miracle of this forest that offers safe passage to a privatized lake. A few of them may follow your example.

Squam Lake via the Chamberlain-Reynolds Memorial Forest trails

Hike distance: 2—3 miles loop (depending on what trails you choose)

Elevation gain: ~100 feet

CLICK HERE for a trail map

As it turns out, the left-center coalition victory in the recent French elections isn’t the only miracle to come out of France lately. I just watched Under Paris, an uncommonly great creature feature about a giant shark that manages to swim up the Seine; just in time for the city triathalon. I’m a connoisseur of creature features—the subgenre that was spawned by the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and the waves of climate anxiety that followed. And let me tell you, Under Paris has it all. A *very* big shark. Suspenseful underwater sequences. Several gruesome kills. A scientist who nobody listens to until it’s too late. A dumb-ass mayor who won’t implement public safety measures because they’re too worried about local tourism revenue. And again, the movie is set in Paris, on the Seine and in some underwater catacombs. Best of all, Under Paris strikes that rare balance between playing it straight-faced and having fun when the opportunity strikes. The ending has to be seen to be believed. It’s bananas! Anyway, Xavier Gens is the director (hats off) and you can stream the film on Netflix.

It’s really getting miserably sticky and sweltering outside. So on top of recommending the publicly-accessible beach on Squam Lake, I’m also going to take this opportunity to indulge in an annual Moss tradition—sharing my old Boston Globe story about the time when I got heat exhaustion while hiking in Baxter State Park and found myself on all fours on the shoulder of the park road, violently and explosively sick, as other cars drove by. I would say “listen to your body” but the thing about heat exhaustion is that it usually sneaks up on you. My best preventative tip is to avoid hiking on a day when the weather is this oppressively humid and hot. Because sweating (your body’s natural cooling mechanism) doesn’t work as well when the local dew point is 100 degrees.

Squam Lake looks so inviting. Another issue is banning swimming in ponds managed by state agencies like Guilder Pond on Mt. Everett in Massachusetts. DCR regulations? Last year signs went up all around this much loved but not crowded swimming hole. “No Swimming”.

Scary about your heat exhaustion. I’ll heed your advice!