Look close enough at any beloved artwork or tradition, and sometimes you’ll find a piece missing; deliberately lost, for political reasons. One of the best examples is the so-called forbidden verses of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” which made the song’s implicit critique of private land ownership pretty explicit. Sing ‘em with me!

”There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me.

The sign was painted, said ‘Private Property.’

But on the backside, it didn’t say nothing.

This land was made for you and me.”

*CHORUS* (we all know this part, hopefully)

“One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple,

by the relief office I saw my people.

As they stood hungry,

I stood there wondering if God blessed America for me.”

There’s a lot happening here, between Guthrie’s condemnation of land hoarding and his observation that the American dream of bootstrapping prosperity is missing a few pieces itself. I’m sure you can understand why these verses were scrubbed from the cultural lexicon via the 1951 recording that millions of us are familiar with. Back then, using the platform of a major record label to explore the darker depths of American capitalism—while not easily done today either—was enough to get you frog-marched before Joseph McCarthy, at the height of his anti-communist crusades. Decades later, the song remains the same. But occasionally, you’ll hear a version with the forbidden verses; exhumed and dusted off for a new generation that relates to Guthrie’s words.

There are holiday traditions with redacted and sanitized origin stories too. This week, my Boston neighborhood is one of hundreds across New England holding a “Holiday Stoll,” in which people put on coats and walk a commercial district well after dark. The streets are illuminated with twinkly lights. The shops and restaurants stay open later than usual. And there might even be caroling or opportunities to meet Santa. It’s the civic equivalent of a creamy peppermint hot chocolate. Nourishing if timed right, and broadly appealing. But you also have to wonder: What if—just as there are sweet and festive drinks made for adults only—there was a holiday stroll that went much harder?

Well….if you happened to live in England during the Middle Ages, you were in luck.

Each Christmas, groups of peasants would liquor up, bundle up, and engage in an activity that you might have heard about in old school holiday jingles—Wassailing. You ventured out into the night with your mates, walked to the nearest feudal lord’s house, and knocked on the door. What happened next is where the history tends to get murky, depending on where you’re getting the story from. Carols such as “Here We Come A-Wassailing” offer a treacly, two-dimensional view of what went down:

”Here we come a-wassailing

Among the leaves so green,

Here we come a-wandering,

So fair to be seen.

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail, too,

And God bless you, and send you

A happy new year,

And God send you a happy new year.

We are not daily beggars

That beg from door to door,

But we are neighbors’ children

Whom you have seen before.”

Now if you skimmed that second verse and thought, “Huh, that’s interesting. I wonder why the wassailers felt like they needed to acknowledge their feudal lord’s disdain for beggars,” you are getting closer. Most carols that invoke wassailing offer listeners the impression that the commoners were out on the town to spread good cheer and offer their best wishes to their employers. And while that’s technically true, it’s not all that the peasants were looking for. Consider the midpoint of the timeless, “We Wish You A Merry Christmas.” A brigade of wassailers has arrived, the door of the manor has just been opened, and the Yuletide cheers have been offered. Now, pay attention to these next two song verses, *especially* the line which is repeated thrice in the second verse:

”For we all want some figgy pudding,

For we all want some figgy pudding,

For we all want some figgy pudding, and a cup of good cheer!

And we won’t go until we get some,

and we won’t go until we get some,

and we won’t go until we get some, so bring it right here!”

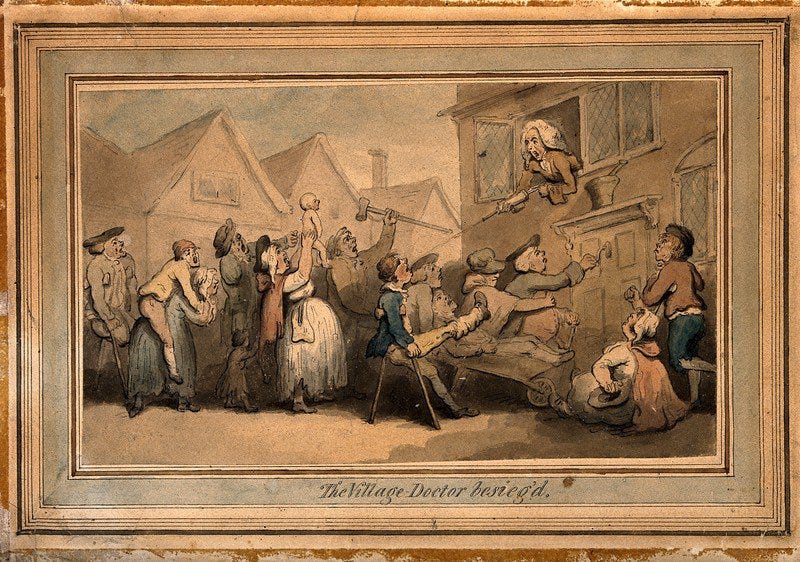

What often goes unsaid whenever we talk about wassailing in 2025 is that the roving bands of peasants—tipsy, merrily rowdy, and sometimes costumed as animals or in cross-dress—wanted some holiday loot from the ruling class. Maybe it was a heaping bowl of figgy pudding, or a more potent holiday cocktail like Lamb’s Wool; a special ale jacked up with cream, sugar, and nutmeg. Savvier lords would have these offerings ready for the wassailers. Because wassailers didn’t take kindly to stingier noblemen. If their entreaties for presents were shot down, the wassailers would hurl insults. And in some cases, they would vandalize the lord’s manor before moving on to the next one!

Now, I want you to perform a thought exercise. Let’s imagine that wassailing had not faded into obscurity after initially being imported to Boston in the 1700s. Assume that this boisterous tradition had continued for centuries, right up to the present day. So here’s your Saturday night agenda for this weekend. You’re meeting up with 15 to 20 friends and neighbors around 6pm, in costume, and pre-gaming with spiced beers or mistletoe margaritas. Then, you’re walking through the flurries together, singing carols on your way to the gates of Robert Kraft’s mansion. The Patriots owner and chairman of The Kraft Group walks to the gate, you offer your songs and dances, and…Kraft has no sweets or elixirs. Well. This is why you all brought spray paint and toilet paper rolls.

Fantasy aside, what intrigues me about wassailing and its lost prominence in English society is how strategic it could be; for the benefit of the ruling classes. If nothing else, wassailing was a short, planned window for the peasants to expel some of their pent-up populist energy before going back to underpaid work for the next 11 months. You might even say that wassailling was an exercise in controlled opposition—a mitigation meant to lower the temperature enough to prevent a full-scale pitchforks and torches revolt from breaking out. That gambit didn’t always pay off for the landowners. The English countryside saw plenty of localized uprisings between the Middle Ages and the 19th Century, when agricultural and economic restructurings brought about the decline of wassailing. But still, a historian could probably argue that wassailing played a role in preserving the social hierarchies that continue shaping U.K. society to this day.

So the question of whether we should revive wassailing—for the lopsided economic dystopia of the 21st Century—may sound like an immediate, “NOPE.” But here’s where I get stuck. Relentless exposure to hardship and cruelty isn’t really pushing the needle. Cathartic as it’s been for millions of us to see or take part in the huge, record breaking-protests against the Trump admininstraiton and the modern oligarchy, we *still* don’t have a formidible opposition party with a tangible and compelling counter-pitch for society. But there is one element of the No Kings protests that I believe offers some navigational guidance. Which element? The creative, frequently funny protest signs.

As my friend and fellow author Jay Heinrichs wrote back in mid-October, the peaceful Velvet Revolution that freed the Czechs from Soviet rule began irreverently, “with kids dressing up like American cowboys and Indians and hoboes.” A lot of the organizing for protests and other direct actions that fueled the revolution took place in venues for merriment like pubs; places where Emma Goldman would have found the kind of singing and dancing that make a revolution worth joining. And I can’t shake the hunch that this is what we’re still missing in the growing American resistance. There are some promising glimmers, like the frog costumes that protesters began wearing in Portland. But there’s a broader unmet need for more laughter, more songs, more costumes, and more mischief. I know that might sound oxymoronic or flippant, given the pervasive danger and demoralizing cruelty of our rulers. But finding ways to blow off steam—merrily, and in festive company—is a challenge that humans have figured out many times before, while suffering hideous repression. And I think we can do this again.

And even in their learned servitude, perhaps the old wassailers were on to something.