A few months ago, I sent out a survey to all Mind The Moss readers to try and get a better sense of where all of you are reading the newsletter from. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of you who responded identified as residents of the northeast United States. (For its first 3-ish years, Mind The Moss was described as a newsletter about “unusual hiking in New England.”) So, I’m going to wager that most of you know at least one person who has left the northeast for less expensive territory beneath the Mason Dixon line; in the broad, solar-poached region that’s known as the Sun Belt.

These days, most Americans reside in metro regions due to the availability of jobs and recreational amenities. And America’s housing affordability crisis is particularly bad in and around cities like New York and Boston which have pretty much been spared from economic shock events and the manufacturing declines that have sent other U.S. cities into long periods of stagnation. These once depressed cities are now attracting those of us who are being priced out of the northeast (and also the west coast cities).

Now, I could take us deep into the weeds of how we got here—our anemic housing construction record, the financialization of housing, and other forces. But I’m going to leave that to the hundreds of other writers who are already untangling those threads.

What I want to tell you about this week is the physical reality of moving and living in a major Sun Belt city during the summer. And two different versions of that city’s future.

Less than two years ago, my friend and former co-worker from the White Mountains, George Heinrichs, relocated from Seattle to Dallas for a new job. He went in with an open mind, aware that things would be very different in Texas, but intrigued by the promise of great food, interesting cultures, and the ground reality of living in the Lone Star State. I decided to go and visit George in Dallas at the height of summer, after he told me about nights when the outdoor temperature was 90 degrees after sundown. I guess you could chalk this up as solidarity between old friends, but I wanted to suffer a few days of a Texas summer with George. I needed to know what 90 at 9pm felt like.

The short and most honest answer is that it’s hellish. You step out into the night from whatever air-conditioned venue you’ve been sheltering inside (which is basically any indoor venue in Dallas) and the fetid, moist air seems to coat every exposed inch of skin and the insides of your breathing orifices. The streetlights are on, the lawns are shining from their latest sprinkling and stirring with tree roaches, and the clicking of woodland cicadas in the branches overhead plays like an overture. That’s the scene if you’re in most residential neighborhoods of Dallas, which can feel more suburban in layout. The city center swaps grass and trees for pavement, and it’s common to see lavishly-dressed people rolling into restaurants and nightclubs long after dark. Why? Because Dallas has been slowly roasting all day, under the big, merciless Texas sky. And it will take all night for that latent heat to start dissipating. People come out at night and they stay out late, before another day of cycling from one indoor, freon accented place to another, almost always by car. Dallas has been built for cars, and during the most blazing months of the year, the city sidewalks often appear empty.

BUT there are exceptions. Consider the Katy Trail, a 3.5-mile greenbelt path that was once part of the Union Pacific railroad line. It runs through the neighborhoods of Oak Lawn and Uptown, northwest of downtown, and it’s flanked with arbors, grassy plants, and shrubs. George learned about the Katy Trail in the weeks before his move from the Pacific Northwest to Dallas, and when I walked it with him for the first time this past year, I was struck by three things. The Katy Trail is the only trail of its kind in the heart of Dallas. People were using the hell out of it. And on the trail, sex was in the air.

One of the peculiar things about Dallas is how it combines the objectification of high fashion hubs like Miami with the conservative values and gender roles that we often associate with the Deep South. A lot of people in Dallas go to great lengths and costs to look their hottest, so that they can establish a family in which Dad brings home the bacon, Mom coordinates the housekeeping, and the debutante ball is just around the corner. Joining the river of humanity on the Katy Trail felt like wandering into a meat parade; a procession of skintight spandex, chemically-enlarged biceps, and surgically-enhanced chests. It’s the only trail I’ve hiked where the scenery made me wonder what my ass might look like if I tried using anabolic steroids, as a lot of folks are now doing.

Now let’s remember, Dallas during daylight hours—in the summer—is excuciating. The abundant pavement turns the city into one big heat island. In some places, you would need a death wish to willingly walk 3.5 miles outdoors in the mid-afternoon. Still, the Katy Trail is reliably active throughout the day. While the peak crowds congregate in the morning and evening, there’s always a range of jacked and tanned denizens on the trail during the toasty interim. Some of them are aiming for the Katy Trail Ice House; a charming beer garden alongside the trail, with plenty of misting fans. Others might be making their way from the gym back to their apartment or house. In other words, the Katy Trail is one of those great urban trails that offers recreation and convenience in one package. And it really makes you wonder. What if Dallas had more walking trails?

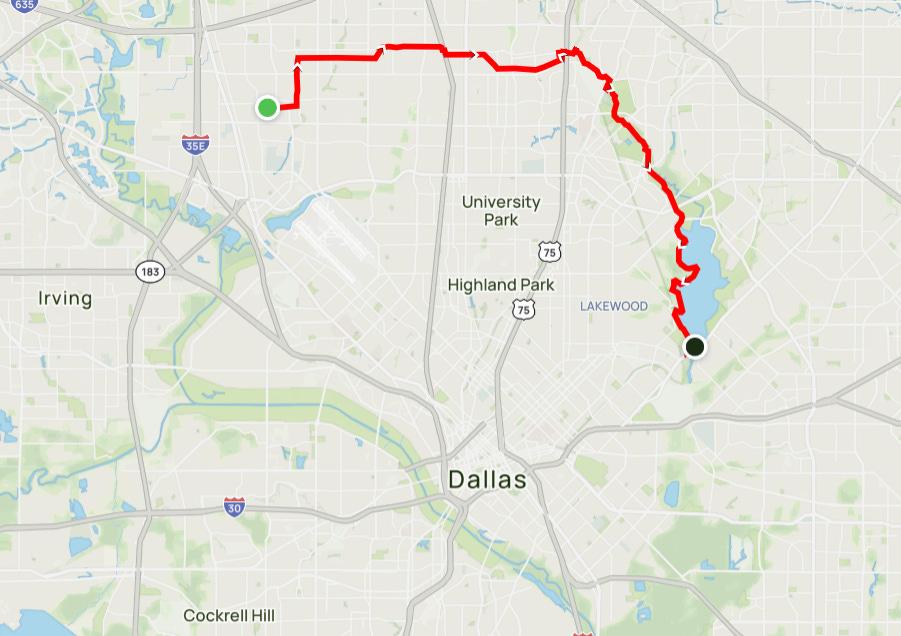

Well, as it turns out, they do. And the other thing that inspired me to visit George in Dallas last weekend was the Northaven Trail. A major escalation of the Dallas Parks Department’s plan to increase multi-modal infrastructure in the city, the Northaven Trail stretches a whopping 9.3 miles through residential burbs on the north edge of town. The trail follows a power line corridor for much of the way before crossing the city’s main highway on a new pedestrian bridge and connecting with the White Rock Creek Trail; a paved walking and biking path that leads to White Rock Lake. (A vast reservoir with waterside paths that are popular for runners, cyclists, and fisherfolk.)

As George and I planned my visit, we grasped the possibilities. From the start of the Northaven Trail, not far from George’s townhouse, we could use the two trails to go all the way to White Rock Lake; a walk of 17.4 miles. In Dallas. In the middle of summer.

If you’re wondering, “Why on earth would you do that to yourselves?” believe me, we asked ourselves the same question aloud the night before, as we filled our daypacks with sunblock, salty snacks, water bottles, and every piece of sun protection gear we owned. And what we kept coming back to was the improbability of something like the Northaven Trail in Dallas. Here was a long distance trail where you could walk, built in an environment where walking for more an hour could kill you. What this signals, on one level, is the cultural impact of walkability in American cities. Even here, in one of the hottest cities in the U.S., policymakers were explorig ways to get Dallas residents out of their cars. The odds were grim, and yet, the Northaven Trail was built. It seemed unlikely that many people would be walking it on a Saturday in August. So George and I decided to be bodies on the trail. Kind of like the three people who went to see Kevin Costner’s Horizon: Chapter 1 in a theater; to show that this was for somebody. Maybe.

We agreed on a 5:30am departure from George’s place, to maximize our time on the Northaven Trail before the Texas sun rose high enough that the homes and the trees along the trail would no longer be able to hold back its glowing wrath. We dressed in shorts, moisture-wicking shade hoodies, and broad brimmed hats. For this hike, I had brought a special sun hat which included a rear neck brim so large that it looked more like a cape. And yet, for the first hour of our trek to White Rock Lake, George and I got incredibly lucky. The projected high for the day was “only” 95 degrees, and the early morning clouds merged with nascent sunlight to create a wondrous backdrop for the walk. The landscape was spare and open, with only the occasional shade tree, and it looked even more epic with the occasional lone jogger or walker passing us, heading out to the vanishing point. For a moment, we felt the magic of urban hiking in Texas.

But the reverie was short-lived. Because by the time we reached a local YMCA and availed ourselves of coffee there, the sun was ascendant and the sweat was already beading on my backside. And this was when George and I noticed something about the Northaven Trail that could be a real challenge for the growth of the trail. Unlike the Katy Trail, which offers plenty of connections to adjacent businesses and residential areas, the Northaven Trail primarily runs through the latter territory. If you live around here and you’re walking your dog—or commuting from your place to a friend’s—that’s fine. But if you’re searching for a trail in Dallas for stretching your legs, finding some new haunts, and maybe grabbing some afternoon delight, the Northaven Trail would probably be a tough sell. It’s long, it’s brutally exposed to the sun, and once you’re on the Northaven Trail, you’re really on it. And you could be on it for a pretty long time.

This became more visceral when George and I approached the Central Expressway, where the new and admittedly impressive pedestrian bridge offered safe passage above 12 lanes of traffic. The trail took us up a winding ramp to the bridge, with no shade whatsoever. The bridge itself was long and meandering, to strike a balance between looking cool and getting across all of those lanes of angry cars. And on the other side, the descent toward the intersection with the White Rock Creek Trail was also shade-free. It was just south of 90 degrees when we crossed the bridge, in full sun. If it had been 10 degrees warmer—which is not uncommon in Dallas—crossing the bridge could have pushed the hike from Type 2 Fun to Heat Exhaustion Medical Emergency. Because you are traversing that bridge for a solid 20 minutes, at least.

As the White Rock Creek Trail took us into a slightly leafier stretch of path along the titular creek, which had that green sheen of Texas waterways that’s uncomfortably ambiguous in origin, I had to ask a question. Is walking sustainable in Dallas? There’s certainly a version of the future in which more of Dallas does exit their cars; in which you can put on your most revealing outfit and go to a singles event on a trail, like the one that a local influencer hosted on the Katy Trail back in June. But this version of Dallas is at least partially dependent on the summers not becoming too much hotter. And by most estimates, summers throughout the United States are moving in a very bad direction. As the journalist Yasmin Tayag wrote about for The Atlantic recently, summers are getting so infernal that a growing number of people are experiencing seasonal depression symptoms that are often associated with the winter months, when longer nights and shivery weather send millions of us indoors. If the average daily high temperature in Dallas keeps climbing, that will start to have an impact on the number of people you see on city trails. The sidewalks might be even emptier. Life in summer could retreat even deeper indoors. On our Northaven Trail walk, George and I saw a tiny fraction of the folks that we had glimpsed walking just a mile on the Katy Trail, during my earlier visit. Most Northaven Trail users were on bikes, to avoid being under the sun for too long. Walking the trail was an adventure, and a penance.

But even out there, we occasionally encountered other walkers. A man with a white handlebar moustache taking his Basset Hound for a stroll. A younger woman who seemed to be doing a workout inspired by Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks. It was a reminder that Sun Belt cities like Dallas, for all their elemental challenges and the specter of climate change looming over all of them, are still crackling with life. A move to the Sun Belt, in this period of climate change, can seem insane. Affordable housing in less sweltering urban areas like Buffalo or Pittsburgh does exist! But the Sun Belt continues to stir something in the imagination, and the City of Dallas’s late breaking effort to bring multi-modal trails to the cityscape feels similarly fueled by an optimistic, irrepressible dream. If we build this, people will come. And they will walk.

It was enough to lure George and I onto the Northaven Trail and the White Rock Creek Trail, which led us to the shores of the manmade lake around noon. And of course, the prophecy was fulfillfed by the Katy Trail’s raging success. Will these trails and others like them lead Dallas into a future that’s less automotive and isolated? A future where you can hop onto a trail to buy some avocados, show off your huge lat muscles and tiny waistline (some call this a Dorito,) and stumble across a new mosaic tile mural?

Maybe we’ve reached the point in our climatological roadmap where that outcome is a fool’s hope. But even if we’re cooked, reality has rarely stopped Americans from doing what they want. If trails are on the menu in Dallas, build them. Some of us will come.

Northaven Trail and White Rock Creek Trail to White Rock Lake

Distance: 17.4 miles point-to-point

Elevation gain: 341 feet

CLICK HERE for a trail map

Back when I commuted from NH to Dallas, I would walk from a downtown hotel to an uptown Starbucks near my office. One time, when I went to order coffee the barista said, "You're the WALKER!" Yep.