The other evening, I pulled on a weighted wool sweater, popped open a bottle of Old Fezziwig Ale, and through the aromas of sweet malt and cinnamon, I realized that this week marks the anniversary of an event that changed the ground realities of American life. We often think of December as the most treacly time of the year—a snuggly slow burn buildup to presents and hugs. But on December 7th, 1941, the United States took the formal step of declaring war on Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Italy and Germany responded by declaring war on the U.S., and just like that, America became a major player in World War II, only a couple days before the winter holidays kicked off.

It’s easy to forget just how much WWII transformed America. Unemployment more or less vanished as the federal government turned the economy into a war production machine, cranking out tanks, planes, surplus equipment, and other essentials. Some production facilities were built anew, and many people (especially women and Black Americans) uprooted their lives to begin jobs in these new factories. But it wasn’t just manufacturing facilities that mushroomed across the American landscape. By 1942, German U-boats had crossed into American waters. Not only did this pose a serious threat to Allied shipping vessels, but it raised the specter of an Axis Powers attack on the U.S. coastline. So the government began fortifying the Atlantic and Pacific coasts with forts and artillery guns. Once the war was over, many of these pop-up sea bases were shuttered and left to be preserved by war history buffs, or abandoned to nature.

In New England, one of the most visible and visitable WWII sea forts is located along the tiny seacoast of southwestern New Hampshire: a brief car or bike ride away from Portsmouth. Odiorne Point State Park, a strange, dreamy collision of tide pools and coastal forests, was once public land. During the war, it was acquired by the federal government and transformed into Fort Dearborn, where a massive battery held a pair of 16-inch/50-caliber guns that were capable of blowing a hole in the hull of a ship. (The power of this artillery unit superseded all other guns in the Portsmouth region.) The guns were test-fired once, but otherwise Fort Dearborn became little more than the answer to a “What if…” question. Since the war, the land has been returned to the state of New Hampshire, and what’s cool about Odiorne Point State Park is how the ruins of the fort itself are not the headlining attraction here. Instead of converting the place into a picnic lawn with a touch of naval infrastructure, the state has allowed the forest and marshes here to reclaim and subsume the lasting pieces of Fort Dearborn.

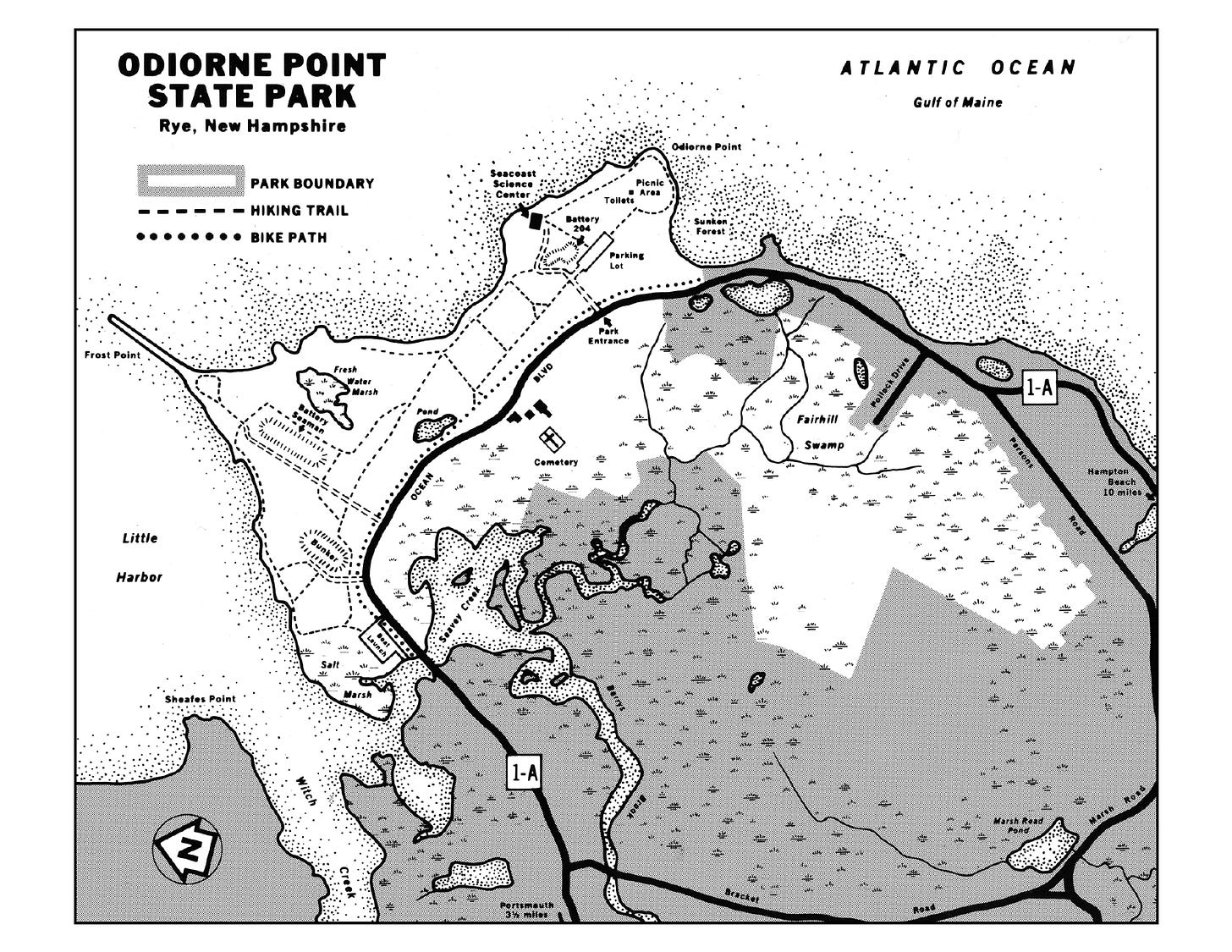

There’s no singular way to hike through the woods, meadows, and beaches of Odiorne Point State Park to visit the fort’s old bunkers and battery structure. Like many state parks, this one offers a constellation of wandering pathways that overlap and split at random. If you’re in the vicinity of the New Hampshire seacoast anytime soon and would like to poke around the fort ruins—in light of the WWII anniversary, or because you have an affinity for semi-creepy places—the best way to orient yourself to Odirone is by considering its two recreational features. At the south end of the park, there’s the Seacoast Science Center, which hosts classes on marine biology and plenty of paved paths along the rocky coast. The quieter north end of the state park has a boat launch and a vast parking lot that connects to the park trail system via an elegant boardwalk.

If winter hiking is your objective, then head for the boat launch parking area and walk south into the spacious coastal woods. The enormous gun battery and the bunkers are tucked in the trees, so if these ruins are your main destination, stick to the paths that run along the west side of the park. As one tends to find, the fort infrastructure has been partially embraced by taggers and the graffiti here can get bold. One of the most recent messages that I saw spray painted on a bunker wall—a message that concerned Trump—is something I’d like to share in this post, but I probably can’t do it without inviting a Secret Service visit. The battery is the most sprawling piece of WWII infrastructure here, and while you’ll have to imagine the Guns of Odiorne attached to the crumbling structure, thirsting for a U-boat, walking around through the belly of the open-air beast still offers a sense of scale when contemplating the war machine that was established during the 1940s and has since been put to more troubling uses.

But to focus on the remains of Fort Dearborn is to miss the forest for the trees. And the pebbly beaches. And the salt marshes. Once you arrive at the Seacoast Science Center campus, at the bottom end of the park, an austere hike through history takes on a more ethereal air as you branch out toward the exposed coastline. If you come here during low tide, be sure to check out the “sunken forest” by the campus. When the tide goes out at the park’s southernmost beach, it reveals a speckling of ancient tree stumps that once constituted a thriving woodland, which was swallowed by the advancing sea roughly 3,500 to 4,500 years ago. If you follow the coastline north, you’ll pass some wonderfully briny and seaweed-festooned tide pools before the rocky footing becomes much sandier—perfect for a slow, meditative winter hike.

While the park’s central stretch of beach contains some impressive driftwood, such as an old door-like structure that looks like the one Rose floated on in Titanic (there was definitely room for Jack on that thing), the scenic pinnacle of Odiorne Point’s coastal territory is the Frost Point breakwater. Breakwaters can be deceptive hiking features. What might look like a simple, flat walk to the end of a man-made stone structure can actually involve a fair amount of rock scrambling and a few leaps of faith, when the stones don’t quite connect. If it’s one of those spattering rainy days, save the Frost Point breakwater for next time. But if the stones are dry and you’re game for some monkeying, give it a shot. Ideally with a heavy, wind-proof jacket.

I’ve been to Odiorne Point State Park on several occasions—first, when I was writing Moon New England Hiking, and other times, with friends, family, and even a date or two. It’s a place that I associate with toasty memories of low-risk adventuring and discovery. It was here, on a beach at the north edge of the park, where a helpful sign introduced me to the clam worm—a beach-dwelling invertebrate that can grow as long as 3 feet. (To avoid these things, don’t visit the beaches at night, when they emerge to dine on small crustaceans.) The remnants of Fort Dearborn were a surprise. For other visitors, those ruins will be the initial gateway into Odiorne Point State Park. But even the most ardent Call of Duty players will probably be humbled by how the landscape has engulfed the relics of those hellish years. The scars of fighting wars of all kinds are still with us. But in the NH seascape, there is a deeper power to be contemplated.

Odiorne Point State Park

Hike distance: Variable, but a loop hike of 2-3 miles is a safe bet

Elevation gain: ~50 feet

CLICK HERE for a trail map

It’s been a bad fall and early winter for the White Mountains when it comes to hiking fatalities. On Monday December 12th, a man who had just climbed Mount Willard fell 300 feet to his death. An avid hiker and an engineer for the Mount Washington Cog Railway, Joseph “Eggy” Eggleston had all of the proper equipment and decades of lived experience when it comes to winter hiking. I mention this because often, when hikers die in the backcountry, there are presumptions about how prepared they were and what they might have done wrong. But the uncomfortable truth is that you don’t really have to do anything “wrong” by the hiker playbook to run into problems on a mountain. Going hiking is an act of calculated risk-taking and I do hope that tragic events such as this one might humble more of us into accepting that eerie reality.

May Eggleston’s memory inspire and humble us all, as we explore this landscape.