In the middle of what was already a harrowing week, replete with accounts of horrific human suffering in Gaza and Israel, something terrible happened in Lewiston, Maine—the deadliest mass shooting in modern state history. The killer, a 40 year-old Army reservist, murdered 18 people at a bowling alley and a restaurant on October 25th. Many were wounded, and that’s before one accounts for the collective injuries of trauma inflicted upon any community where this uniquely American tragedy occurs.

While mass shootings have become a cornerstone of American life—a new normal sustained by gun manufacturers, their lobbyists, and the politicians they continue to buy—New England has been relatively spared from the consistent rise of shootings that have left thousands dead, permanently disabled, and/or bereaved. The trauma of the Lewiston mass shooting is a trauma that New Englanders are less experienced in suffering. And while this makes the shooting all the more shocking for many of us to comprehend, it also presents us with a juncture and a choice. Do we just try to move on? Or do we channel this unfamiliar horror and grief into creating a different future?

One of the cruelest impacts of these regular mass shootings is the amnesia effect they have on us. We absorb each event with disgust, until the next mass shooting happens. And in the process, the people whose lives have been changed by recent shootings are largely forgotten. In a country where people have to crowdfund their medical bills, this can have grave implications for survivors who suffered life-altering wounds. But for a community devastated by a shooting, the amnesia effect can also be quite brutal. Multiple residents of Buffalo expressed as much to ABC News earlier this year, recalling how quickly the national spotlight swung from the shooting of 10 Black residents at a local grocery store to the school massacre in Uvalde, Texas.

“We’re looking for somebody, but nobody’s coming in to save us,” Garnell Whitfield Jr. told ABC, adding that “this is about looking inwardly. Any changes that have ever happened in the world are because humans got together and connected in some way.”

As many Mainers themselves have suggested in recent days, the social intimacy and solidarity that exist between Maine’s cities and towns (which is kind of remarkable for such a large and loosely populated state) will prove invaluable in the months ahead, as Lewiston recovers from this unprecedented tragedy. As a regular visitor to Maine, based in Boston, I’ve been thinking about how New Englanders can contribute to that sense of solidarity between regional communities that might seem distant or remote, but are actually just a couple hours away by car or train. And what I’d like to encourage you to do this week, the following week, or during the year ahead, is quite simple.

You should go for a hike in Lewiston.

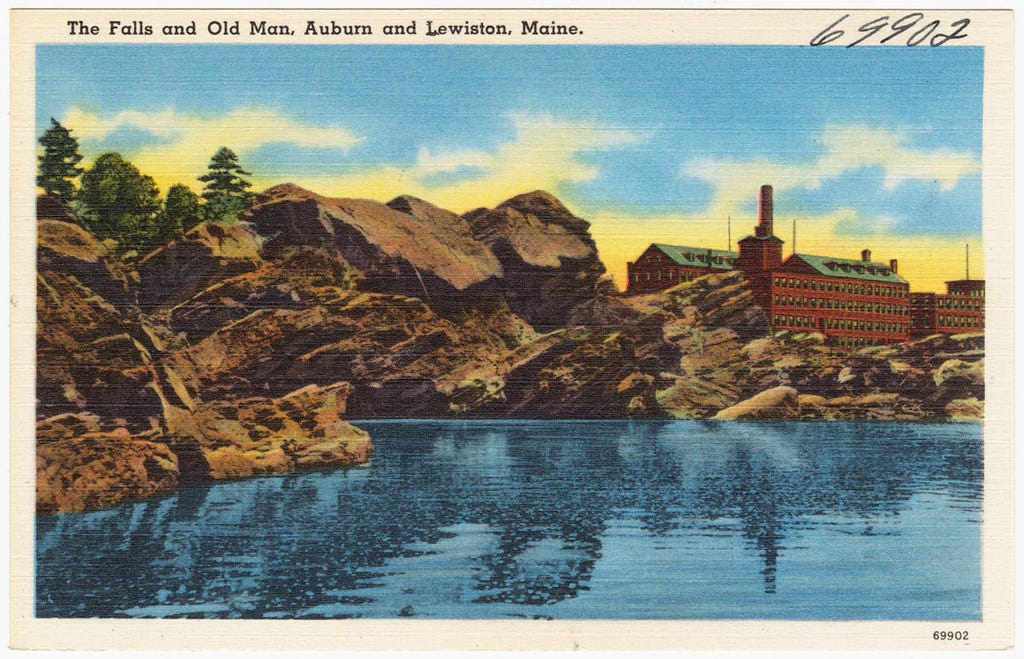

When I say that, the operative words are “in Lewiston.” Because Lewiston happens to be built on the mighty Androscoggin River, which rumbles through the state’s piney interior from the White Mountains to the sea. From the northern end of the Lewiston and Auburn Riverwalk, which ambles along the river past historic mill buildings, you can gaze out toward Great Falls, a frothing torrent of whitewater that reflects the grandiosity of Maine’s landscape. Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the river the East Coast Greenway bike path that spans from Florida to Maine runs along the east shore through the greenery of Sunnyside Park and Riverside Cemetery. Sometimes, the big natural feature of a city can be so superlative that the city can’t help but build itself around that feature. That’s certainly the case with New Haven and its traprock mountains, which I wrote about last week. And in Lewiston, the river runs through it all.

It would be one thing if these Androscoggin-adjacent pathways of Lewiston merely offered stellar river views. But in fact, there’s something even more beautiful that you can regularly find here: something I’ve seen on prior visits to Lewiston, that I’m vividly reminded of this particular gutting week. There’s always somebody out on these paths, savoring the special ambiance of the Androscoggin and enjoying a reprieve from the commerce and development that surround the waterway on both sides. Lewiston is Maine’s second most populous city, with 37,121 residents as of 2020. The riverways are natural cross-pollination sectors from the many people who call Lewiston home, from resettled Somali refugees to Bates College students to random visitors like myself, whose introduction to Lewiston involved a can of Baxter Brewing Stowaway IPA. (The brewery is perched over the river and it’s a natural stop for any urban hike.)

As Frederick Law Olmsted often noted, the power of public green spaces and blue spaces is not just their ability to bring people together: it’s the way they allow people to witness others coming together. This was a salient observation in the wake of the Civil War, when Olmsted was designing Central Park. And I think it holds something of value for us today, as we reel from these communal tragedies that tear people apart.

Even when you venture outside the city center of Lewiston, you can experience the same thing that inspired Olmsted. In 2018, when conducting field research for my first hiking guidebook, I found my way to Androscoggin Riverlands State Park, located 20 minutes north of downtown Lewiston. While it’s technically in the nearby town of Turner, these riverside woodlands are basically to Lewiston what the Blue Hills Reservation is to Boston—a shared haven for recreation, inquiry, and serenity. The spider web of rugged trails that run through the 2,675 of mixed woodlands are used seasonally by hikers, runners, ATV riders, skiers, snowmobilers, and more. And unlike other shared-use forests, where I’ve sometimes felt outnumbered (and unwelcome) by the visitors on motorized vehicles, I found the rustling pathways of Androscoggin Riverlands to be a wonderful venue for a more social kind of hiking. I traded plenty of nods, conversed with an older couple about a mossy stone wall near the water’s edge, and at one point, I asked an ATV rider if I was still on the Bradford Loop Trail. The 12 miles of river frontage gave the space a tangible scenic connection to the nearby City of Lewiston, but these interactions really made the park feel like a city green space.

None of this is to suggest that Lewiston somehow needs visitors to heal from the tragedy that’s shaken the community. That’s the sort of condescending supposition that Maine is already used to hearing with regard to the economic hardship in the regions that used to be imbued with paper mill wealth. But given Maine’s true, self-affirmed reputation as a state where many residents value old school ways of kindly engaging with each other, and looking out for one another during hard times, I think it’s worth reminding ourselves that we are capable of these acts. The trails of Lewiston are spaces where I have been reminded of it. Without that sense of solidarity—and the possibility that comes with it—we will never overcome the powers and the structural forces that continue catalyzing tragedies like mass shootings. There’s one way out of this situation. To find it, we need to re-find each other and remember what we share.

Maybe that happens on a riverside pathway at the end of stick season, with the frost creeping back into the night. Or at the end of a bar top on a lonesome Tuesday, with the hiking poles stashed in a car. Wherever, whenever, it’s something to seek out. Now.

CLICK HERE for a map of the Lewiston-Auburn Greenway

CLICK HERE for a map of the East Coast Greenway in Lewiston

CLICK HERE for a map of Androscoggin Riverlands State Park

Given that this week’s newsletter is shaped by recent news events, I don’t really have any other hiking news to share here. But I have been re-visiting this song from Neil Young lately, and it hits differently this week. It feels like where we’re at right now.

Maybe you’ll find something in it too.