The next time you’re splayed out on a picnic blanket at your favorite park, or huffing some essence of azaleas at a community garden, take a moment to consider how much we’ve recovered from the Industrial Revolution. Back in the late 19th Century, when textile mills and steel plants speckled the shores of our lakes and rivers, cities were literal shitholes. Most of the manufacturing plants were powered by coal-burning steam engines whose emissions billowed from smokestacks, shrouding the cities in smog. Oil, debris, and other industrial wastes were dumped in waterways. And as if the factories weren’t wreaking enough havoc, lots of city residents had to take sewage disposal into their own hands, due to the lack of indoor plumbing at the time. The Ned Flanders types would take pails of odorous refuse to a designated dumping site, and everyone else would just fling their turds out the windows, pedestrians be damned.

Leafy and flowering parks where you could escape the cacophony and squalor—as envisioned by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux—were the cure for this mass scale poisoning. And while New York may have gotten the party started with Central Park and Prospect Park, few American cities leaned into public parks like Chicago did. By the time Al Capone and Eliott Ness were in a shooting war with each other during the Prohibition era in the 1920s, Chicago had constructed so many parks and gardens that the city motto was Urbs in Horto, which is Latin for “City In a Garden.” And yet, the City of Chicago is more like the nucleus of an extremely large and colorful atom. The city is surrounded by an expanse of green and blue space, with Lake Michigan to the east and a labyrinth of woods, wetlands, and creeks wrapping around the other sides.

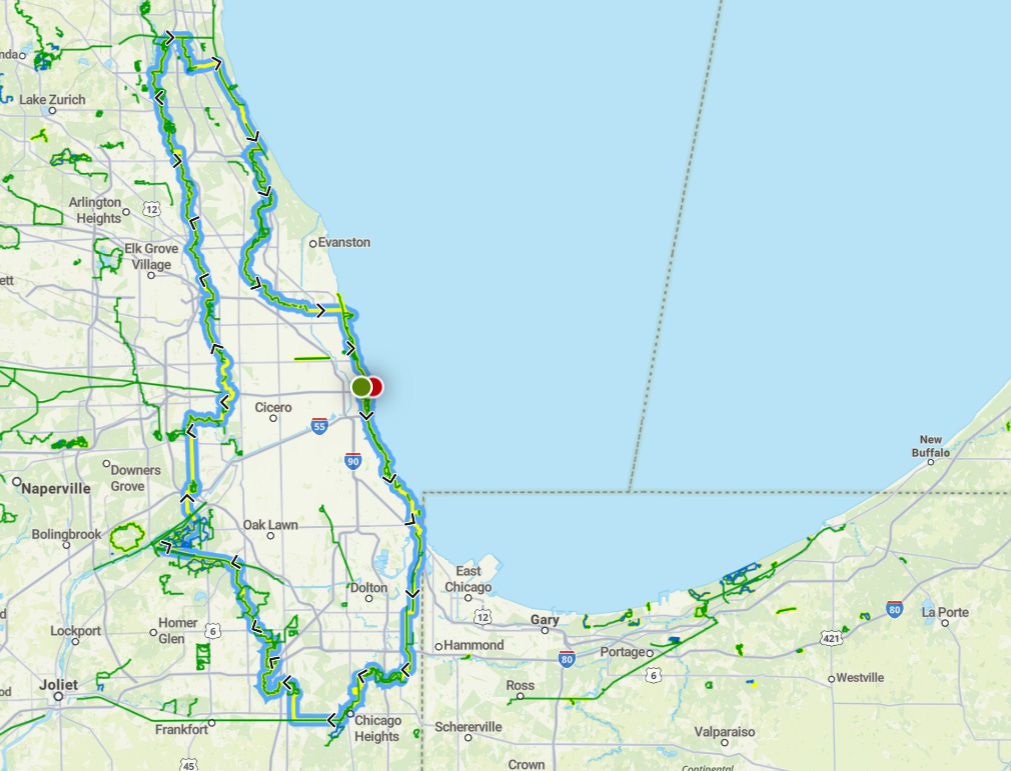

A couple of years ago, I learned that you can thru-hike around this landscape. You set off from Buckingham Fountain in the city center. You follow 210 miles of paths and streets. And when you finally make it back to the lakeshore and gaze across the water at the high-rises of downtown Chicago again, you have become a different person; toughened by the chigger bites, the sunburns, and the thorns embedded in your pants. How is this possible? Because back in 2017, local explorers created the Outerbelt Trail, which forms this sprawling circle around the City in a Garden and Cook County.

And last week, I spent 48 hours thru-hiking part of this trail with one of the architects.

As in, hiking the trail, sleeping in a tent along the trail, and hiking onward the next day.

This is, to put it mildly, something that you cannot do in most American metro areas.

Just like the San Francisco Crosstown Trail and Boston’s Walking City Trail, Chicago’s Outerbelt Trail is a patchwork of walkable paths through forest preserves, meadows, and other green spaces flanking the city. One of the people who spent innumerable hours investigating these trails and finding the places where they run into each other is Jay Readey; a lawyer, social entrepreneur, and president of the Outerbelt Alliance, which steers the Outerbelt project. As Jay explained to me during our first collegial phone call a few months ago, the Outerbelt route was sculpted by the notion that you could follow waterways to Lake Michigan and the city. And some of these waterways and smaller water bodies along the Outerbelt are legal camping areas. I use the term “legal” because lately, a number of cities have been enacting tent-camping bans; as a response to more people becoming homeless and living in tent encampments. It’s an unfortunate type of posturing that doesn’t actually address the roots of the issue (the cost of housing and health care) while at the same time taking something away from everyone. Learning that you can actually sleep in a tent in the Chicago metro area, as part of an overnight backpacking trip, was all that it took for me to call Jay again and ask if he and any of his friends felt like a midsummer expedition on the Outerbelt Trail.

”Let me ask you something,” Jay said, a few days before I boarded a plane to Midway. “How backcountry do you want this to be?”

”What do you mean?” I asked.

”Well, when it comes to meals, we could coordinate and pack our own food,” Jay said. “Or…since you’re visiting…we could truck some local delicacies into the campground.”

”Oh.”

”The nature preserve where we’ll be camping is only five minutes up the road from Aurelio’s, which is the pope’s favorite place for thin-crust pizza. Or so they’ve said.”

There was a pause as I imagined tucking into a pepperoni pie steps away from my tent, as a fuschia sunset flared through the trees and the mosquitoes stirred to life.

”Backcountry is overrated,” I finally said to Jay.

The Outerbelt was designed with connections to the city center in mind, and after spending my first night in The Loop, I rose at sunrise, I put on my bulkiest backpack (which was stuffed to the hilt with camping gear), and I walked over to Union Station to catch a Metra train to Calumet; on the south side of the city. For our thru-hike, Jay and his comrades had selected a long and winding piece of the Outerbelt that runs through some of the bushier and lonelier woods around the city—woods where the trails are maintained somewhat passively and are prone to plant overgrowth during summer. Jay met me at the train station, pulling up in a well-weathered pickup truck plastered with bumper stickers that serves as the official Outerbelt Alliance service vehicle and goes by the name Trucky Truck Truck. Our hiking companions for the day were newly-minted graduates from Wheaton College who were spending the summer working with Harvey Conservation Corps—an AmeriCorps-funded program focused on revitalizing parks, community gardens, and preserved green space in the Chicago area.

Since this was city thru-hiking—as opposed to the Spartan purity of backcountry thru-hiking—we decided to make things easier for ourselves by loading some of our heftier camping gear into one car and leaving it at the Homewood Izaak Walton Preserve; our destination for the day’s end. Less encumbered (a wise idea, given that temperatures were climbing into the low 90s), we piled into Trucky Truck Truck and motored over to the northeast tip of Lansing Woods; a snarly parcel of forest where we picked up the Outerbelt. The hike began on a deceptively cushy note, as we followed a paved biking and walking path into a sun-splashed field. Then, Jay indicated that it was time for us to veer left onto a less-traveled path. At a glance, the entrance to this path appeared invisible. I was staring at a wall of dense vegetation that would almost certainly leave a rash if you weren’t wearing protective clothing. But then, through the leaves, I saw a little pink flag planted in the ground. These flags have been continually installed along shaggier sections of the Outerbelt as low-impact and low-cost trail markers. And sure enough, after we pushed through the barrier of leaves, we stepped onto a legible path.

Now, I’ve logged a considerable amount of mileage on urban trails, and most of them occupy a solid middle ground between the extremes of built environments and natural environments. On some trails, you might occasionally wander through a more extreme built space, like the outer edge of a cat food factory or a pavement-heavy area that’s short on shade trees. But the Outerbelt Trail is the first urban trail I’ve hiked that offers you a taste of the natural world at its most extreme. The ribbon-like paths that we took through Lansing Woods were a testament to the regenerative power of local plants. It wasn't long before we were wading through tall grasses and leafy plants that looked a lot like stinging nettle. Occasionally the flora towered over our heads. While some of the pink flags planted in Lansing Woods had been removed, enough remained to help us avoid losing the trail. Another affirmation that we were on the right track was a lone elderly gentleman who we crossed paths with on the periphery of a reedy meadow. He was out for a daily ramble, sporting an enviable bucket hat and undaunted enough to be out there in shorts. (The rest of us had worn protective trail pants, at Jay’s urging.)

The woods provided essential shelter from the full heat of the day, and as we crossed a busy road from Lansing Woods into North Creek Meadow Forest, two things were becoming clearer. The first was North Creek itself; one of the Outerbelt’s numerous trailside waterways, bound for Lake Michigan. But the other thing was the amount of grueling work that went into not just scouting the Outerbelt loop, but revisiting many of its pieces and keeping the brushiest bits visible. Adam and Erik, two of the Harvey Corps. workers along for the hike, had actually spent the last few days re-visiting the segments on which we were walking; to gauge any obstacles like trees blown down during a storm or poison ivy overgrowth. In some places, this must have felt like bush whacking, which...well…if you’ve ever bush whacked, you’ll know how tough it can be.

The forests through which we were hiking are managed by the Forest Preserves of Cook Country, but “managed” might be a generous way of describing how the trails through the forests are maintained. For his part, as one of the Outerbelt’s principal creators and advocates, Jay understands the constraints that the FPCC faces, which seem to stem from liability concerns. (In 2014, Chicago Fire actor Molly Glynn was killed in a freak accident when a tree fell onto her during a bike ride in suburban woods north of the city.) “But here’s the thing,” Jay explained to me. “The FPCC also makes it clear that hikers can go anywhere in any preserve, with the caveats that they’ll be traveling at their own risk and should practice a ‘tread lightly’ ethos. So there’s a lot of latitude for people to reclaim prior trails or to go where the deer blaze trails.” The permanence or sustainability of those trails, as Jay sees it, just depends on awareness and traffic. The awareness part is harder without the ability to place signs on the trails with FPCC permission. But in the current era of GPS maps and apps, physical trail signs aren’t as essential as they once were. The visibility of the Outerbelt Trail really depends on more hikers using the shorter paths that it’s made of. Regular use makes the paths more accessible and inviting, and the Outerbelt Alliance seeks to get more people using them; while at the same time supporting the mission of the FPCC by promoting minimally invasive land use ethics. “We want to support the trail without overwhelming the sanctity of the FPCC, which hosts the trail,” Jay said.

The timing of our conversation about ethical land use was curious, as we were only a stone’s throw from Thornton Quarry; one of the world’s largest aggregate quarries, at 1.5 miles long and 450 feet deep. An eye-popping place of extraction, which you can see from Interstate 294, the quarry will remain an active harvesting site for another 200-ish years. (After which it could be rewilded.) But the quarry is also home to the Thornton Reservoir; a floodwater storage space connected to an extensive network of underground tunnels that run beneath the adjacent suburbs. The idea here is that if you can concentrate abundant rainwater and all of the shit that it picks up, then it’s less likely to end up in Lake Michigan, recreational green spaces, or your basement. The reservoir project is a more utilitarian demonstration of how industrialized space can be leveraged to do something more ecologically responsible; just as the parks and preserved woodlands that we now hold dear turned cities into livable places.

The Homewood Izaak Walton Preserve—which we staggered into at 4pm, soaked with sweat and covered in forest detritus—is flanked by railroad infrastructure. You would never know this, given the immensity of the trees, the prominence of the natural sand dunes that you can glimpse here, and the serenity of the onsite ponds where visitors come to fish long after sundown. But the preserve is one of innumerable examples of what’s possible, when it comes to reclaiming and re-greening land in urban areas. We had to detour slightly away from the Outerbelt Trail to reach the preserve, and being able to camp there for the night was something that Jay had negotiated. But if you’re thru-hiking the Outerbelt, you’ll find more reliable camping options at trail-adjacent spots like Camp Bullfrog Lake in Willow Springs, or Camp Shabbona Woods in South Holland. Some of these campgrounds even have cabins, and while getting there may require a quick rideshare lift from the trail, the Outerbelt Alliance is working on making these trailside tenting zones more visible for subsequent waves of urban thru-hikers.

Where does it all lead? What’s the lasting outcome of this collective labor, beyond the Outerbelt Trail itself? It’s too soon to know, but what’s thrilling about the Outerbelt Trail is how much Jay and his comrades are going for it and grasping for the full extent of what urban hiking can look like. As I occupied one of the bathrooms, stripping down and giving myself a sponge bath with wet wipes before changing into fresh clothes, I realized I had never done anything like this before. And the next morning, we would do it all over again, with a new team of Harvey Conservation Corps, on even less traveled paths in these south side woods. It was tough to conceive of this as I emerged from the bathroom, just in time to catch Jay heading toward one of the picnic tables with a giant box from Aurelio’s Pizza in hand. I was exhausted, in the best way. We made fast work of the pizza, seizing upon it like a pack of Velociraptors as the sun went down. I had to trust that a night of tossing and turning in my sarcophogus-like tent would be enough to have me recharged and ready for Round 2 the next morning. But just to be safe, at Jay’s recommendation, we decided to end our night with one last indulgence.

We squeezed into Trucky Truck Truck and crunched out of the parking lot, as two cars driven by night fishermen arrived. We drove past rows of single family homes, with the windows down so that we could feel the muggy breeze on our bare skin. Five minutes later, we were standing in line at the local Dairy Queen; a lone source of luminance in an otherwise darkened part of the cityscape. Other people were gathered there too. A few of us took our frappes and floats over to a gigantic tree on the edge of the parking lot, and we sat on a wooden fence beneath the branches, which felt like the arms of an old god hovering over us. We were in the garden. And yet, we were still in the city.

To learn more about the Chicago Outerbelt Trail, including hiking advice, CLICK HERE.

I also recommend this story by Diane Penningroth, a writer and copy editor at Midwest Living who decided to circumnavigate the entire 210 mile trail. To read it, CLICK HERE.

What a great story; my first trip to Chicago in 1954 was a depressing jolt -downtown buildings were dirty and grimy. Last summers visit there was a wonderful experience, wish i had known about this trail.

This is so cool! I've only been to Chicago once -- for an Avon Walk -- and I loved it!

I've been wanting to tell you about this post from another blogger I follow. It's about a series of parks that have been created in Seoul, South Korea. If you're ever interested in looking outside the US for urban hiking experiences, this might be a place to visit!

https://fashionschlub.com/2025/06/20/daehyeonsan-rose-garden-beauty-in-seouls-concrete-jungle/